Private market marks, say hello to public markets – Financial Times

It’s always fun to imagine what might happen to certain private valuations if they were ever exposed to the glare of public markets. Today, we have a chance to gawk at the reality.

Let’s recap a saga that Alphaville has been idly following but not yet covered (it’s been a busy year, OK). Bluerock is a New York-based alternative asset manager. Back in 2012, it launched a fund to invest in private real estate — the Bluerock Total Income+ Real Estate Fund.

Given the illiquidity of the underlying assets and the leverage it was permitted to use, Bluerock structured it as an “interval fund”. This means that investors could only redeem some of their money a quarter, up to a cap. Beyond that and they’d have to wait.

For almost a decade all was well, but then the $3.6bn fund got whacked by rising interest rates. It lost 11.5 per cent in 2023 and 6.6 per cent in 2024. Investor requests for withdrawals quickly started piling up, with the fund unable to meet them all. The WSJ’s Jason Zweig covered the saga this summer with his usual skill.

Since then, Bluerock has received shareholder approval to convert the vehicle from an interval fund to a listed closed-end fund, and renamed it the Bluerock Private Real Estate Fund, or BPRE.

The company’s marketing docs talk a lot about how this is an “opportune time” for a “transformative step” that will give it “investment freedom” to take advantage of “an extremely attractive time to deploy capital”, but also nods to the more concrete reason for the conversion:

Importantly, listing the Fund, and thereby providing for liquidity via the secondary market rather than through direct redemptions of shares, is intended to help prevent the Fund itself from becoming a “forced seller” of its underlying semi-liquid real estate-related assets. This preserves the integrity of the underlying investment strategy for all shareholders, providing the portfolio management team with greater flexibility and fewer cash constraints, all which should generally be accretive to performance, with the goal of maximizing shareholder value.

For obvious reasons, there’s been a lot of interest in how BPRE might trade when it finally makes its stock market debut. As Accredited Investor Insights’ Leyla Kunimoto wrote in her Substack last week: “Once the fund starts trading, we’ll all find out what the public market thinks about the NAV marks on the private assets sitting inside this vehicle.”

Today, we have the result, with BPRE finally making its debut on the New York Stock Exchange. Trading is still live, but at pixel time BPRE’s shares are trading at $15.12. That’s up from the $14 opening, but compares to the investment fund’s net asset value yesterday of . . . $24.36.

That’s a 38 per cent markdown in one day. According to Alphaville’s rudimentary napkin math, this has now almost wiped out the last of the cumulative returns that the fund made since its inception.

In statement Bluerock’s CEO Ramin Kamfar said that the whole ‘private market marks are unrealistic’ refrain was popular but inaccurate in this case.

I think the discount you are observing is temporary and event-driven as shares exchange hands from pent-up sellers to willing buyers. BPRE’s early discount to NAV tracks the same experience that you can see if you research other comparable funds that have listed – i.e. that they generally open trading at a discount, but that the discount closes to NAV over a reasonable period of time as the pricing more closely converges with the value of the fund’s underlying assets.

That dynamic is because selling demand immediately presents itself upon listing, but buying demand generally plays out over time as sophisticated investors wait out peak selling to try to purchase at the most attractive market bottom price. And then as the fund’s shares trade out of pent-up sellers’ hands to willing buyers, the fund discount closes over time.

So what are BPRE’s assets? Well, it has actually invested in what looks mostly like 35 underlying real estate funds managed by the likes of Prologis, CBRE, Ares. Carlyle, and Brookfield. The single biggest exposure — at 15.8 per cent of gross assets — is to IQHQ, a private Californian real estate investment trust that specialises in life sciences real estate.

BPRE says the underlying assets constitute well over 5,000 properties, of which a shade over 40 per cent in industrial sites, 20 per cent in residential, 19 per cent in speciality real estate, and 17 per cent in debt, with the balance in office and retail. But really, this is a fund-of-funds in drag. In retrospect, an expensive private real estate interval fund-of-funds was very ZIRPy.

What is the wider readthrough here? Well, the massive immediate public market discount applied to the Bluerock Private Real Estate Fund’s NAV is at least partly stoked by the fact that there had been a lot of unmet investor withdrawal requests. Investors now have liquidity, albeit at a price they probably don’t like.

Nor does it necessarily mean that Bluerock’s marks are massively off-base. As Kamfar points out, Investment trusts, REITs, closed-end funds and other structures like them routinely trade at a discount to their NAV. We’ll have to wait and see where the shares settle once the initial investor exodus is over. Kamfar told us that he hoped the discount would close over the next “several quarters as willing buyers take over from willing sellers”.

In its investor FAQ, Bluerock promised that it will do everything it can to support its share performance, up to and including scrapping the whole darn conversion (zoomable version).

However, a 38 per cent markdown on the first day of trading . . . well, it isn’t great, is it? And it’s hard not to think that this isn’t an entirely unique saga either.

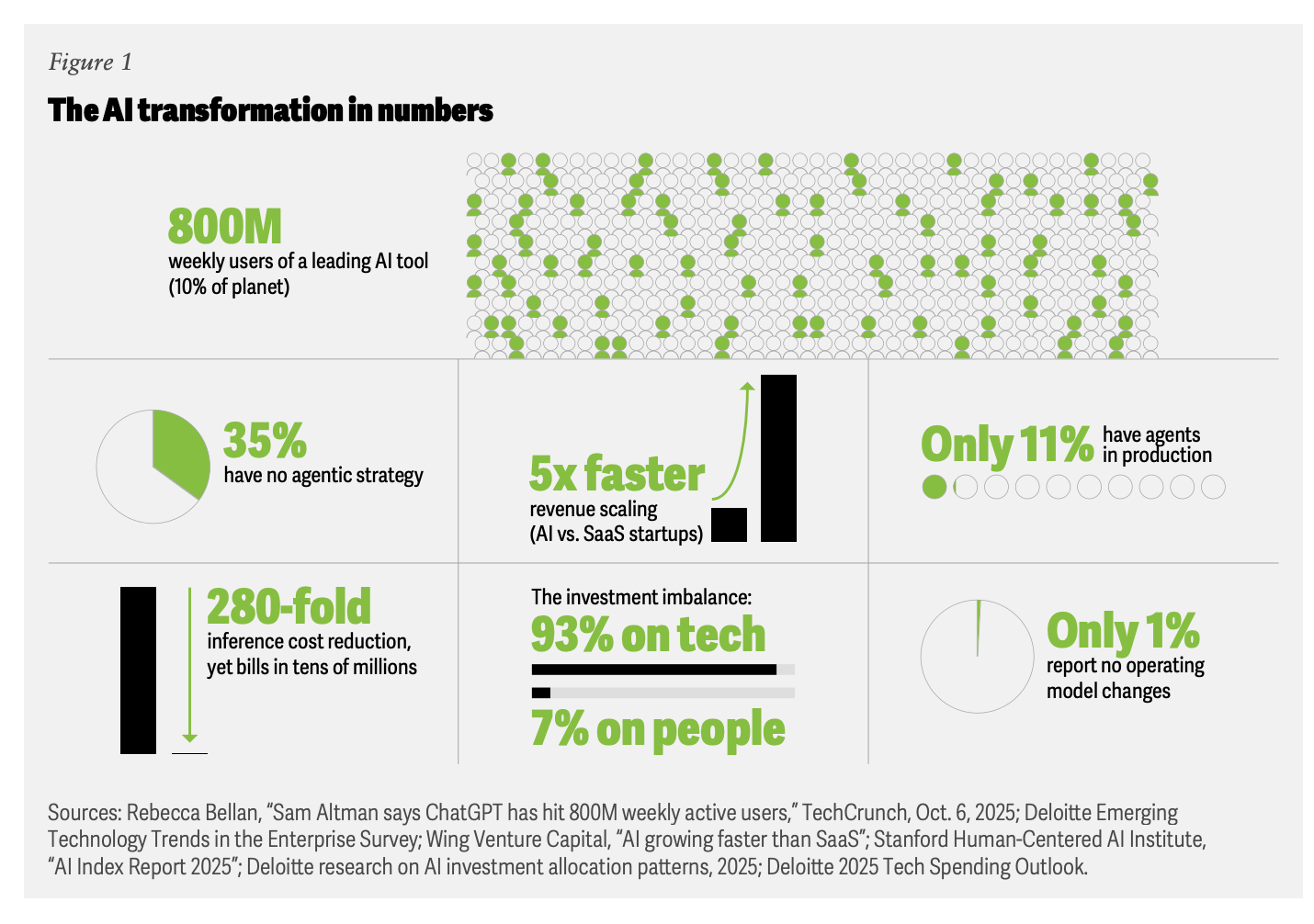

After all, there’s a reason why private equity seem reluctant or unable to bring a lot of their investments to the public markets despite equities booming, and instead are having to resort to financial sleight-of-hand to generate cash to hand back to investors.